The Heap

On this page:

The heap is an area of memory that your program uses when it wants to dynamically allocate space for data. While using the heap gives you a considerable amount of flexibility, your program must manage this resource. That is, the program must explicitly allocate and deallocate this space. In contrast, the program does not allocate or deallocate memory in other areas.

Because allocations and deallocations are intimately linked with your program’s algorithms and, in some cases, the way the program uses this memory is implicit rather than explicit, problems associated with the heap are the hardest to find.

Finding Heap Allocation Problems

Memory allocation problems are seldom due to allocation requests. Because an operating system’s virtual memory space is large, allocation requests usually succeed. Problems most often occur if you are either using too much memory or leaking it. Although problems are rare, you should always check the value returned from calls to allocation functions such as malloc(), calloc(), and realloc(). Similarly, you should always check whether the C++ new -operator returns a null pointer. (Newer C++ compilers throw a bad_alloc exception.) If your compiler supports the new_handler operator, you can throw your own exception.

Finding Heap Deallocation Problems

TotalView can let you know when your program encounters a problem in deallocating memory. Some of the problems it can identify are:

free() not allocated: An application calls the free() function by using an address that is not in a block allocated in the heap.

realloc() not allocated: An application calls the realloc() function by using an address that is not in a block allocated in the heap.

Address not at start of block: A free() or realloc() function receives a heap address that is not at the start of a previously allocated block.

If a library routine uses the program’s memory manager (that is, it is using the heap API) and a problem occurs, TotalView still locates the problem. For example, the strdup() string library function calls the malloc() function to create memory for a duplicated string. Since the strdup() function is calling the malloc() function, TotalView can track this memory.

TotalView can stop execution just before your program misuses a heap API operation, which allows you to see what the problem is before it actually occurs. (See How TotalView Intercepts Memory Data .)

realloc() Problems

The realloc() function can either extend a current memory block, or create a new block and free the old. When it creates a new block, it can create problems. Although you can check to see which action occurred, you need to code realloc() usage defensively so that problems do not occur. Specifically, you must change every pointer pointing to the memory block that was reallocated so that it points to the new one. Also, if the pointer doesn’t point to the beginning of the block, you need to take some corrective action.

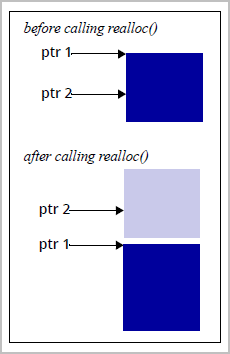

In Figure 178, two pointers are pointing to a block. After the realloc() function executes, ptr1 points to the new block. However, ptr2 still points to the original block, a block that a program deallocated and returned to the heap manager.

If you use block painting (See Example: Viewing Painted Memory), TotalView can initialize the first block with a bit pattern. If your program is able to display the contents of this block to you, you’ll be able to see what kind of problem occurred.

Memory Leaks

A memory “leak” describes a block of memory that a program allocates that is no longer referenced. For -example, when your program allocates memory, it assigns the block’s location to a pointer. A leak can occur in one of the following cases:

You assign a different value to that pointer.

The pointer was a local variable and execution exited from the block.

If your program leaks a lot of memory, it can run out of memory. Even if it doesn’t run out of memory, your program’s memory footprint becomes larger. This increases the amount of paging that occurs as your program executes, making your program run more slowly.

Here are some of the circumstances in which memory leaks occur:

Orphaned ownership—Your program creates memory but does not preserve the address so that it can deallocate it at a later time.

Consider this example:

char *str;

for( i = 1; i <= 10; i++ )

{

str = (char *)malloc(10*i);

}

free( str );

In the loop, your program allocates a block of memory and assigns its address to str. However, each loop iteration overwrites the address of the previously created block. Because the address of the previously allocated block is lost, its memory can never be made available to your program.

Concealed allocation—Creating a memory block is separate from using it.

Because all programs rely on libraries in some fashion, programmers are responsible for allocating and managing memory. As an example, contrast the strcpy() and strdup() functions. Both do the same thing—they copy a string. However, the strdup() function uses the malloc() function to create the memory it needs, while the strcpy() function uses a buffer that your program creates.

In many cases, your program receives a handle from a library. This handle identifies a memory block that a library allocated. When you pass the handle back to the library, it knows which memory block contains the data you want to use or manipulate. There may be a considerable amount of memory associated with the handle, and deleting the handle without telling the library to deallocate the memory associated with the handle leaks memory.

Changes in custody—The routine creating a memory block is not the routine that frees it. (This is related to concealed allocation.)

For example, routine 2 asks routine 1 to create a memory block. At a later time, routine 2 passes a reference to this memory to routine 3. Which of these blocks is responsible for freeing the block?

This type of problem is more difficult than other types of problems in that it is not clear when your program no longer needs the data. The only thing that seems to work consistently is reference counting. In other words, when routine 2 gets a memory block, it increments a counter. When it passes a pointer to routine 3, routine 3 also increments the counter. When routine 2 stops executing, it decrements the counter. If it is zero, the executing routine frees the memory. If it isn’t zero, another routine frees it at another time.

Underwritten destructors—When a C++ object creates memory, it must have a destructor that frees it. No exceptions. This doesn’t mean that a block of memory cannot be allocated and used as a general buffer. It just means that when an object is destroyed, it needs to completely clean up after itself; that is, the program’s destructor must completely clean up its allocated memory.