Editing an Expression

On this page:

Edit an expression in the Data View by double-clicking inside any field to make the text editable. You can enter any expression into the Name field, changing a variable’s name, type, or value.

Dereferencing a Pointer

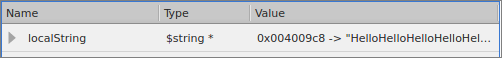

When you dive on a variable, it is not dereferenced automatically. To dereference it so you can see its target, edit the expression. For example, for this pointer to a string:

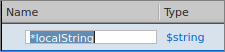

Double-click in the Name column to make the text editable, and then dereference the pointer:

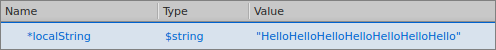

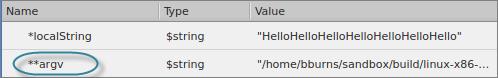

The Data View displays the variable’s value:

For argv, i.e. a pointer to a pointer, dereference it twice.

Changing the Value of Data

If your data’s value is not what you expect, you can change a variable’s value to test a fix. The new value changes the source code for that session only. If you kill the program and restart it, the previous value is reinstated.

Double-click on the value in the Value column and enter a new value.

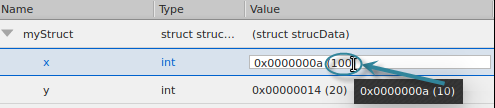

For example, this example changes the value of x from 10 to 100:

Casting to Another Type

You may need to cast your data to a type that is more meaningful. Enter the cast code in the Type field. Here are some examples.

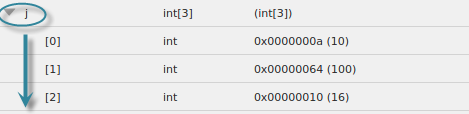

Casting to an Array in the Data View

Cast a variable into an array by adding an array specifier to the Type declaration. For example, adding [3] to a variable declared as an int changes it into an array of three ints.

Press Enter to cast the variable:

Depending on the array declaration, TotalView displays arrays differently. See Displaying Arrays.

Displaying an Allocated Array

Display an allocated array. Using malloc() (in C and C++) creates a pointer to allocated memory. For example:

dynStrings = (char**) malloc (10 * sizeof(char*));

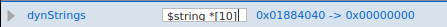

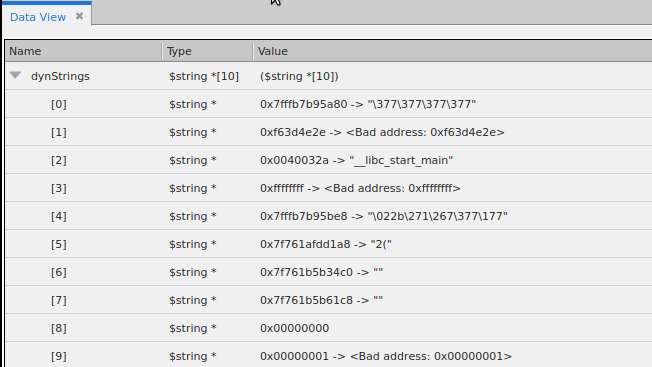

Because the debugger doesn’t know that this is a pointer to an array of ints, to display the array, change its type to $string *[10].

Then click the down arrow to display your array of 10 strings.

Built-InTypes

TotalView provides a number of predefined types. These types are preceded by a $. You can use these built-in types anywhere you can use those defined in your programming language. These types are also useful in debugging executables with no debugging symbol table information. The following table describes the built-in types:

|

Type String |

Language |

Size |

Description |

|

$address |

C |

void* |

Void pointer (address). |

|

$char |

C |

char |

Character. |

|

$character |

Fortran |

character |

Character. |

|

$code |

C |

architecture-dependent |

Machine instructions.The size used is the number of bytes required to hold the shortest instruction for your computer. |

|

$complex |

Fortran |

complex |

Single-precision floating-point complex number.The complex types contain a real part and an imaginary part, which are both of type real. |

|

$complex_8 |

Fortran |

complex*8 |

A real*4-precision floating-point complex number.The complex*8 types contain a real part and an imaginary part, which are both of type real*4. |

|

$complex_16 |

Fortran |

complex*16 |

A real*8-precision floating-point complex number.The complex*16 types contain a real part and an imaginary part, which are both of type real*8. |

|

$double |

C |

double |

Double-precision floating-point number. |

|

$double_precision |

Fortran |

double precision |

Double-precision floating-point number. |

|

$extended |

C |

architecture-dependent;oftenlong double |

Extended-precision floating-point number. Extended-precision numbers must be supported by the target architecture. In addition, the format of extended floating point numbers varies depending on where it's stored. For example, the x86 register has a special 10-byte format, which is different than the in-memory format. Consult your vendor’s architecture documentation for more information. |

|

$float |

C |

float |

Single-precision floating-point number. |

|

$int |

C |

int |

Integer. |

|

$integer |

Fortran |

integer |

Integer. |

|

$integer_1 |

Fortran |

integer*1 |

One-byte integer. |

|

$integer_2 |

Fortran |

integer*2 |

Two-byte integer. |

|

$integer_4 |

Fortran |

integer*4 |

Four-byte integer. |

|

$integer_8 |

Fortran |

integer*8 |

Eight-byte integer. |

|

$logical |

Fortran |

logical |

Logical. |

|

$logical_1 |

Fortran |

logical*1 |

One-byte logical. |

|

$logical_2 |

Fortran |

logical*2 |

Two-byte logical. |

|

$logical_4 |

Fortran |

logical*4 |

Four-byte logical. |

|

$logical_8 |

Fortran |

logical*8 |

Eight-byte logical. |

|

$long |

C |

long |

Long integer. |

|

$long_long |

C |

long long |

Long long integer. |

|

$real |

Fortran |

real |

Single-precision floating-point number.When using a value such as real, be careful that the actual data type used by your computer is not real*4 or real*8, since different results can occur. |

|

$real_4 |

Fortran |

real*4 |

Four-byte floating-point number. |

|

$real_8 |

Fortran |

real*8 |

Eight-byte floating-point number. |

|

$real_16 |

Fortran |

real*16 |

Sixteen-byte floating-point number. |

|

$short |

C |

short |

Short integer. |

|

$string |

C |

char |

Array of characters. |

|

$void |

C |

long |

Area of memory. |

|

$wchar |

C |

platform-specific |

Platform-specific wide character used by wchar_t data types |

|

$wchar_s16 |

C |

16 bits |

Wide character whose storage is signed 16 bits (not currently used by any platform) |

|

$wchar_u16 |

C |

16 bits |

Wide character whose storage is unsigned 16 bits |

|

$wchar_s32 |

C |

32 bits |

Wide character whose storage is signed 32 bits |

|

$wchar_u32 |

C |

32 bits |

Wide character whose storage is unsigned 32 bits |

|

$wstring |

C |

platform-specific |

Platform-specific string composed of $wchar characters |

|

$wstring_s16 |

C |

16 bits |

String composed of $wchar_s16 characters (not currently used by any platform) |

|

$wstring_u16 |

C |

16 bits |

String composed of $wchar_u16 characters |

|

$wstring_s32 |

C |

32 bits |

String composed of $wchar_s32 characters |

|

$wstring_u32 |

C |

32 bits |

String composed of $wchar_u32 characters |